At the March graduation ceremony, 126 students from the Africa Centre for HIV/Aids Management received their Postgraduate Diploma in HIV/Aids Management (PgDip) – the centre’s flagship programme that was presented for the first time in 2001. The value and relevance of this programme in understanding, managing and combatting Aids in the world of work and wider society go far beyond book knowledge, as is evident from the feedback from a few graduates.

Gaps and opportunities in the fight against HIV and Aids

The course takes a multifaceted approach to the HIV/Aids pandemic, covering a wide range of topics across the medical, socioeconomic, cultural and business fields. This ensures that all students – whatever their line of work – acquires knowledge and skills they can apply directly in their role.

Blaise Lukau, a medical doctor who works as the SaDAPT (Same Day ART in Presumptive TB Patients) study co-ordinator and physician at SolidarMed in Lesotho, found the Management in the era of HIV/Aids module particularly valuable: “I now have a better understanding of the ways in which strategic HR management could contribute to decision-making in organisations, while considering the impact of pandemics such as HIV/Aids and Covid-19 on the workforce.”

For Mekolle Julius Enongene, learning about the socioeconomic impact of HIV and Aids was an eye-opener: “It presents the disease beyond being a biological phenomenon.” Enongene works as a consultant and technical specialist with FHI 360, a global organisation dedicated to finding solutions to global challenges, in Cameroon.

Nothemba Nqayi, an assessment officer at SU’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, found it enlightening to understand the potential impact of making medicine and (mobile) clinics available at the workplace: “It eradicates missed appointments and medication non-adherence, improving the wellbeing of staff. In addition, it is time- and cost-efficient for both employees and employers.”

One of the graduates, Chambalson Chambal – who also holds two master’s degrees – will be moving on to the Africa Centre’s PhD programme. He works as an engagement officer at UNOPS in Mozambique, which supports peace and reconciliation efforts and improves health services in the country. An abstract he submitted to the American Society of Microbiology Conference which was inspired by one of the course assignments is informing his PhD research. “My doctoral research will focus on HIV policy, specifically the perceptions of public health professionals toward HIV criminalisation among certain groups.” Chambal explains that there is a scarcity of HIV criminalisation literature tailored to the Southern African and Mozambican contexts and that current research employs outdated procedures that do not reflect the latest biomedical advances.

The proof is in the pudding: practical application in the world of work

Many of the graduates have already started applying their newly acquired knowledge in their jobs. According to Lukau, he is now able to design and implement clinical research programmes aimed at improving healthcare for people living with HIV. Enongene has been using his skills to facilitate strategic planning, manage productivity and monitor performance on HIV projects.

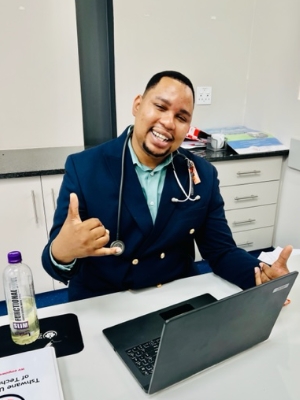

Noko Lucky Morakaladi’s job as a clinical nurse practitioner at the Tshwane University of Technology involves disseminating health-related information: “The postgraduate diploma has been my stronghold in disseminating evidence-based information on issues relating to HIV and Aids and has assisted me in analysing current data and formulating policy.”

The global north-south divide and the 2030 target

While Covid-19 has overshadowed – and in many cases set back – efforts to fight HIV and Aids, there is still a UN target to end Aids by 2030. Is this achievable? Most of the graduates agree that it is possible, but that it will require considerable effort, investment and commitment at government, private sector and civil society levels.

Zooming in on Africa, where most of the students reside, the outlook becomes less optimistic. As Enongene points out, “Commitment to research towards vaccines and access to innovative therapy will be especially required in the global south, which is home to almost 70% of the HIV burden.”

Nikki Soboil, who works in South Africa’s public healthcare sector, names dysfunctional healthcare systems, barriers to access and stigmatisation as key stumbling blocks for Africa. For Morakaladi, lack of knowledge about PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) as one of the most effective HIV prevention strategies is a concern. “That is why I chose a health education role at an academic institution, because when you educate the youth, you are educating the future citizens.”

Despite the challenges, people like these graduates continue to dedicate their time and effort to improving the HIV outlook. Studying while working full-time and managing family life will always require discipline, commitment and sacrifice. But as Nqayi aptly states: “It is worth it in the end, because I can now be useful to my family, community and workplace.”